Departmental History

Part 1. From the Beginnings to the Post-Civil War Closing in 1871

Part 2. From the Reopening of the University in 1875 to the 1920s

Part 3. From the 1920s to the 1960s

Part 4. From 1966 to the Present

Part 1. From the Beginnings to the Post-Civil War Closing in 1871

On Jan. 10, 1794, a year before UNC opened its doors, the University’s Board of Trustees met to establish policies and programs for the new institution. One of their items of business was to set the courses of study and tuition for each. Among the courses they decided upon were “Latin, Greek, French, English Grammar, Geography, History and Belles Lettres,” at $12.50 per annum. Latin and Greek have thus been a central part of the University’s curriculum from its very inception, although not the most expensive: Geometry, Astronomy, Natural Philosophy, and other science courses were also offered, at a cost of $15 per year.

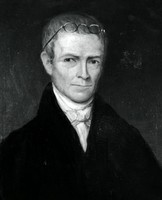

For many years after the first student, Hinton James, arrived in February of 1795, both the number of faculty and the number of students were small, and professors and tutors were expected to teach a wide range of subjects, from the languages to the sciences. Among the early faculty who specialized in the ancient languages were Archibald DeBow Murphey, after whom Murphey Hall is named, and William Hooper, who graduated from the University in 1809, was awarded an AM in 1812, and taught Latin and Greek from 1817 to 1822 and 1827 to 1837.

It is not until 1838 that we find the appointments of separate professors of Latin and Greek: John DeBerniere Hooper, who taught Latin from 1838 to 1847 and Greek from 1875 to 1884, and, in Greek, Manuel Fetter (1838-1868). Although we hear of a few Master of Arts degrees being conferred in these first eighty years, it is clear that in the period before and during the Civil War the University was above all an undergraduate school, and a practical-minded one at that: agriculture and mining were among its offerings. Much of the teaching in this period was in the hands of tutors, who were usually recent graduates of the University who taught for a year or two and then moved on.

Part 2. From the Reopening of the University in 1875 to the 1920s: The Establishment of a Modern Research University

The University closed entirely from 1871 to 1875 during Reconstruction, but when it reopened it entered a period of expansion, and of transformation into a modern research university, that lasted some fifty years. The department evolved along with the institution as a whole. The University announced the formation of a “graduate department” (an early forerunner of The Graduate School) in the late 1870’s, and the first post-Civil War graduate degrees were awarded soon thereafter, in 1883. The earliest graduate degrees in ancient studies that we have been able to find so far are an MA by Samuel Bryant Turrentine in 1884 (thesis: “Affiliation of Roman and Greek History;” this does not seem to be extant and may have been done in the History Department) and a PhD by Thomas James Wilson (“The Genitive of Quality and the Ablative of Quality in Latin,” 1898). A real graduate program in Classics, with substantial numbers of graduate students, did not begin, however, until the 1920s.

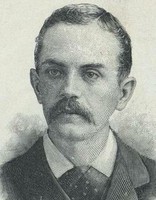

The arrival of Eben Alexander from the University of Tennessee in 1886 was an important moment for ancient studies in Chapel Hill, for during his time as professor of Greek at Chapel Hill (1886-1893 and 1897-1909) Alexander taught ancient Greek, served as the University’s first Dean of Faculty, and for many years supervised the University library. It was in this period that the University acquired its first purpose-built library, the Carnegie library now known as Hill Hall, and Alexander also served on the committee that brought to Chapel Hill the young librarian Louis Round Wilson, who developed the library into one of the South’s premier research facilities. One of Alexander’s students was William Stanly Bernard, who joined the faculty as instructor in Greek in 1901, was promoted to professor in 1920, and continued to teach Greek until his death in 1938. Bernard, himself a memorable character, was joined by George Howe (1903 to 1935) and Gustavus Adolphus Harrer, both Latinists. Harrer, a Princeton PhD, came to Chapel Hill in 1915, taught Latin, including Latin epigraphy, and was awarded a Kenan Professorship in 1934. James Penrose Harland (like Harrer a Princeton Ph.D.) came to Chapel Hill in 1922 as the department’s first archaeologist and by 1929 had been promoted to full professor. He traveled widely in Greece, excavated on Aegina, and developed a large collection of lantern slides illustrating the classical world and its art.

Meanwhile, the department acquired a new and, as it turned out, permanent home: Murphey Hall, which was designed to house the language and literature departments, was begun in 1922 and completed in 1924. John Nolen, the first planner called to the University during World War I, set out a plan of extending the original campus southwards beyond South Building. Work began with the architecture and construction of the Eastern Arm of South Campus: Saunders, Manning, and Murphey Halls.

Thus, by the mid-1920s, the department had the faculty and facilities to develop a strong graduate program: there was a core of four outstanding faculty (augmented by others who served for shorter terms or as visitors), a modern new teaching facility, and, from 1929, the new Wilson Library, just a moment’s walk from Murphey Hall. Chapel Hill rapidly became one of the most important centers of research and graduate study in the South, and the department’s collection of theses and dissertations, which begins in the 1920s, can serve as an accurate reflection of this new direction and role.

Part 3. From the 1920s to the 1960s: The Foundations of the Modern Department and Berthold Ullman

In the 1930s, the department continued its basic mission of teaching Latin, Greek, and Classical Archaeology to undergraduates and a small number of graduate students. Howe continued as chairman and professor of Latin until 1936, Bernard until 1937, Harrer until 1943, and Harland until 1963. A more active period — effectively a new department — began when Berthold Ullman became Kenan professor and chairman of the department in 1944. Ullman was a dynamic presence, even beyond his retirement in 1959. A distinguished scholar of medieval and renaissance palaeography and manuscript traditions, he also co-authored an extremely successful Latin high school textbook series.

He encouraged the study of Latin both at the university and in the secondary schools of North Carolina. Preston H. Epps, who had taken the Greek chair in 1943, became Kenan professor in 1955. Under Ullman’s leadership, the department expanded with the addition of Walter Allen in Latin (1945) and Henry Immerwahr in Greek (1957). In addition, there were increasingly close links with other departments. Wallace Caldwell, for example, was made professor of Ancient History in 1930 and continued in that position until 1945.

In 1958, Robert J. Getty, a Scot and a highly respected scholar on Lucan, was invited from Canada to become the first Paddison professor of Latin and chairman of the department. His successor as chairman (1959-65) was Albert I. Suskin, a North Carolinian who attended UNC as both an undergraduate and graduate student and taught in the department from 1936 until 1965, except for his period of service in the Army (1942 to 1945). In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the department under Suskin’s leadership made many new appointments: Charles Henderson, Kenneth J. Reckford in 1960, Hubert Martin and Edwin L. Brown in 1961, and Philip A. Stadter in 1962.

Berthe Marti joined the department in 1963, taking early retirement from Bryn Mawr to assume a half-time professorship of classical and medieval Latin. She continued and strengthened the program in medieval studies, adding a doctoral degree in that area. Also in these years, the department was chosen to be the first American office of L’Année philologique, an indication of its increasing international visibility.

In 1965, T. Robert S. Broughton succeeded Getty, who had died in the fall of 1963, as Paddison professor of Latin. He set up the University Library’s special study room for epigraphy and palaeography, established the Ph.D. program in Classics with Historical Emphasis, and encouraged close cooperation with the Department of History, and in particular with the Roman Historian Henry C. Boren. When Albert Suskin died in office as Classics chair in 1965, Henry R. Immerwahr served as interim chair for 1965-66 and oversaw the search that brought George A. Kennedy to Chapel Hill to take over as chair.

Part 4. From 1966 to the Present: George A. Kennedy and Beyond

The University expanded from some 10,500 students in 1963 to over 20,000 in the following decade, and the Department of Classics expanded along with it. Two new professors, Emeline Hill Richardson in Classics and Sara Immerwahr in Art, jointly directed a new doctoral program in Classical Archaeology. Two new Paddison Professors were named in 1970, Brooks Otis in Latin and Douglas C. C. Young in Greek. The department introduced new graduate courses on Greek palaeography alongside those on Latin scripts. On the undergraduate level there was an extensive expansion of the curriculum. Under Kennedy’s tenure as chair (1966-76) the department thus expanded its scope and expertise; after Kennedy, Philip Stadter (chair 1976-1986) and G. Kenneth Sams (chair 1986-1996) oversaw further growth and development.

Along with the University as a whole, the Classics department turned to fund-raising in a serious way in the mid-1990s, and in the past decade it has established several substantial endowed funds in support of both undergraduate and graduate students and faculty. These are in addition to the Paddison Fund, which was created in the 1950s and now provides at any one time for two or three distinguished professorships and contributes a substantial amount to the University’s research library. Newer funds or endowments include the Cassas Fund, which supports the Nicholas A. Cassas Term Professor of Greek Studies; and the University’s William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust, which supports the Kenan Eminent Professorship of Classics; the Kenneth Reckford Fellowship, which provides funding for a graduate student for five years; the Berthe Marti Fellowship, which supports a year of work on a dissertation at the American Academy in Rome; and the J.P. Harland Endowment Fund in Classical Archaeology, which helps graduate students participate in archaeological fieldwork.

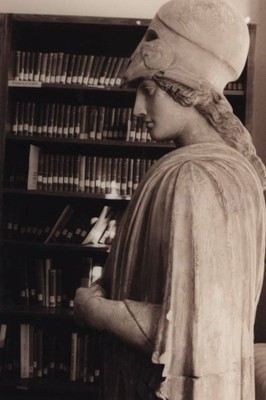

In 2001 and 2002 Murphey Hall underwent a multi-million dollar renovation and restoration project, including the Ullman Library, which currently contains some 10,000 volumes, and the Archaeology Seminar Room.

The Archaeology Seminar Room (Murphey 304) houses the Department’s collection antiquities, which consists of some 130 whole objects and hundreds of fragmentary artifacts from various periods and culture. The Department’s holdings were recently greatly enhanced by the Crist Collection, a gift from Dr. Takey Crist that included a unique assemblage of Cypriot antiquities now on display in the Seminar Room and used for teaching and hands-on training in undergraduate and graduate seminars.

In terms of personnel and curriculum, the department has developed in a number of directions. While the history of archaeology at UNC begins with the appointment of J.P. Harland in 1922, the addition in the 1960s and 1970s of Emeline Hill Richardson, G. Kenneth Sams, Gerhard Koeppel, and Marie-Henriette Gates in Classics, as well as of Sara Immerwahr in Art, created for the first time a substantial core of archaeology faculty. Since the 1960s the archaeology faculty has conducted extensive fieldwork in Italy, the Aegean, eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Ken Sams was project director from 1988-2013 of the excavations at Gordion. In 2002 Donald Haggis began directing excavations at the Early Iron Age and Archaic site of Azoria on Crete (American School of Classical Studies at Athens), and more recently Jen Gates-Foster has joined the French Mission to the Eastern Desert in Egypt (Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Le Caire).

Berthold Ullman had long ago provided a first impetus to post-classical studies, and the department has maintained that interest through appointments in Latin palaeography and medieval and Byzantine studies.

The past 25 years has brought about many changes in the department. George Houston (chair 1996-2001) succeeded Sams and was followed by William Race (2001-2003), James O’Hara (2003-2007), Cecil Wooten (2007-2012), and James Rives (2012-2020). In this period a number of long-term faculty who had directed scores of dissertations retired: Ed Brown, Gerhard Koeppel, Philip Stadter, Kenneth Reckford, Jerzy Linderski, Bill West, Sara Mack, George Houston, Carolyn Connor, Peter Smith and Cecil Wooten. Our deans supported the department with replacement positions, as the total number of students at the University grew to 30,000. Donald Haggis (Aegean archaeology) was appointed in 1993 to replace Marie-Henriette Gates, who moved to the Department of Archaeology at Bilkent University. Bill Race (1996-2016) was hired as Paddison Professor of Classics; Michael Weiss (1994-2001) renewed the department’s traditional strength in linguistics; Sharon James brought new expertise in gender and Latin poetry (1999), James O’Hara was hired as Paddison Professor of Latin (2001), and Monika Truemper (2005-2013) came to teach Hellenistic and Roman art and architecture. Nicola Terrenato (1998-2007), Maura Lafferty (2000-2006), Phiroze Vasunia (2003-2005), Werner Riess (2004-2011), and Brooke Holmes (2005-2007) brought new life to Murphey before moving on to positions at Michigan, Tennessee, Reading, Hamburg and Princeton. The College of Arts and Sciences again supported the department with positions, and in 2006-2008 the department hired six new faculty members: James Rives, Kenan Eminent Professor of Classics, works on Roman religion and Latin historiography; Robert Babcock on Latin paleography and Medieval Latin; Brendan Boyle (2007-2012) on Greek political and ethical thought and rhetoric; Emily Baragwanath on Greek historiography; Owen Goslin (2008-2015) on Greek tragedy; and Lidewijde de Jong (2008-2012) on Roman archaeology. Under James Rives’ eight-year chairship, several new hires were made. Luca Grillo (2013-2018), teaching Latin historiography and rhetoric, and Jennifer Gates-Foster, Hellenistic and Roman Mediterranean archaeology, joined the faculty in the fall of 2013. Janet Downie, a specialist in Second Sophistic and Imperial-era literature, was hired a year later, to be followed by Al Duncan (Greek Drama) and Hérica Valladares (Roman art and literature), who joined the department in the fall of 2015. In 2017, Patricia Rosenmeyer, a specialist in archaic Greek poetry, epistolary fiction, and epigram, became the Paddison Professor of Greek. More recently, Suzanne Lye (Homer, Greek literature and culture) and Timothy Shea (Greek archaeology) joined the faculty in 2018 and 2021. Donald Haggis became department chair in 2020.

In 1999, under the leadership of George Houston, the department created our Post-Baccalaureate Program, which provides a flexible course of study for students who want to improve their skills either for their own education or as preparation for graduate work; many have gone on to M.A. or Ph.D. programs at UNC or at other top schools. Since 2003, the department has been developing an exchange program with King’s College London, the UNC-King’s Strategic Alliance, which provides opportunities for undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty to study and collaborate with their peers at King’s College London. The department played a key role in the creation of a new major and minor in Archaeology, which started in 2008 and is organized through the Curriculum in Archaeology. The Duke-UNC Consortium for Classical and Mediterranean Archaeology, a close collaboration between Mediterranean archaeologists at both institutions, offers further possibilities for interdisciplinary dialogues. This consortium also offers students access to seminars, excavations, and other research opportunities, as well as academic advising at both universities. The department also contributes to the Program in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, which brings together more than 60 faculty members from 10 departments in the humanities and fine arts who conduct research on the period from the fall of the western Roman empire to the eighteenth century.

In addition to our full-time faculty members, the Classics department has several part-time instructors and adjuncts in the departments of Anthropology, Art, English and Comparative Literature, History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies. Among those who have made significant contributions to Classics are Mary Sturgeon, professor of Classical Art (appointed 1977 and retired in fall 2013); Richard Talbert, William Rand Kenan, Jr., Professor of History (1988); Eric Downing, Hanes Distinguished Term Professor of German, English and Comparative Literature (1995); archaeologist Jodi Magness, Kenan Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence in Early Judaism (2002); and C.D.C. Reeve, Delta Kappa Epsilon Distinguished Professor of Philosophy (2005).

Current course offerings — in Classical Archaeology, Classical Civilization, Greek, and Latin — present a diversity of perspectives on and approaches to the ancient world, catering to various majors and degrees, as well as undergraduate, post-baccalaureate, and graduate education.

A complete list of all Ph.D. dissertations and M.A. theses in Classics completed at UNC since 1894 is available online; a list of graduate alumni and their current positions can be found on the Alumni page.